2022 Economic Outlook: Moving Toward the Next, New North Carolina

By Dr. Michael Walden

Professor and Extension Economist Emeritus

Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, NC State University

Review of 2021: A Good Year

Although all the final numbers are not in, it appears North Carolina experienced a very good economy in 2021. The recovery from the Covid-19 recession continued and generated impressive gains for the state economy. The big questions are, will the good news continue in 2022, and is the stage being set for the next new North Carolina?

In 2021, aggregate production of goods and services (GDP) increased at an annual rate of 4.5% (through the third quarter, the latest available). This was better than the national rate of 3.8% and was greater than the 2.6% rate in the state during the pre-pandemic year of 2019. Sectors adding the most production were leisure/hospitality, health care, finance and technology. Sectors lagging in growth included personal services and education. The North Carolina economy is now 3% larger than its pre-pandemic level.

There were also impressive gains in the North Carolina labor market in 2021. The state added a record 143,500 net new jobs. The leading job gains were in leisure/hospitality, professional services, manufacturing and construction. The average hourly wage rate also increased 6.8%; however, after subtracting inflation, the gain was only one-half percent.

Several metropolitan regions in the state have fully recovered their job losses from the pandemic. Greenville, Hickory, Durham-Chapel Hill, Jacksonville, Raleigh-Cary and Wilmington are now either at or above their pre-pandemic employment levels. Asheville and Greensboro-High Point still trail their pre-pandemic job highs by 5%.

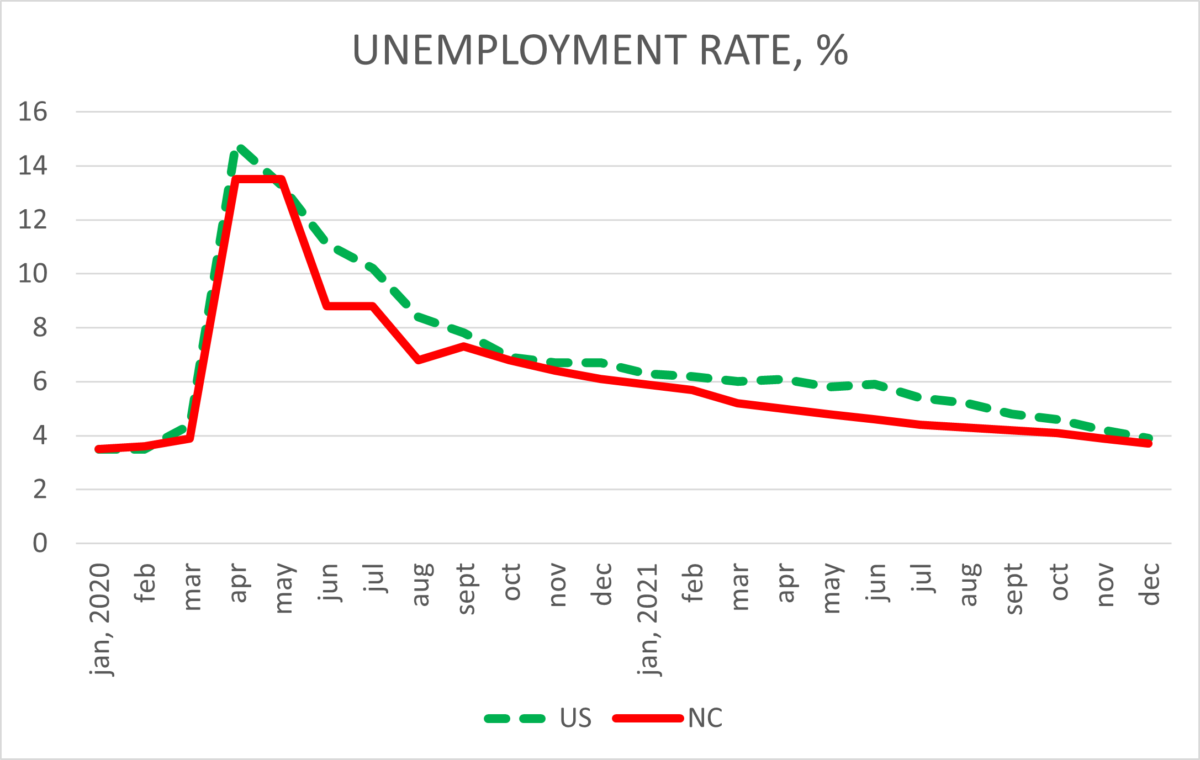

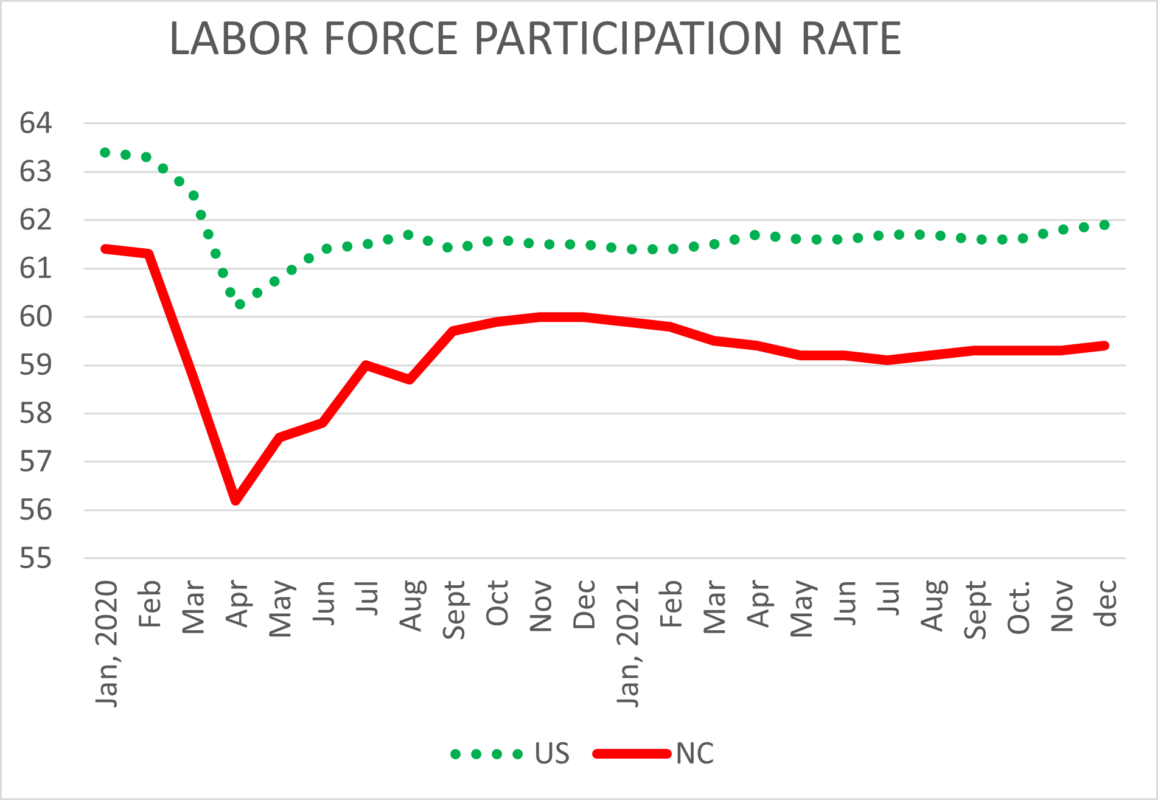

Despite the overall progress in the labor market, there are lingering issues. Total statewide jobs are still 47,000 less than their pre-pandemic level. And although the unemployment rate dropped to 3.7% in December (Figure 1) and is not far from its level before Covid-19, the percentage of available individuals who are of working age and either have jobs or are looking for jobs is smaller than two years ago (Figure 2). If labor force participation was the same as two years ago, over 100,000 more people would have been in the labor force at the end of 2021.

The smaller labor force is one of the reasons behind labor shortages in selected economic sectors. Other factors behind the labor shortfall are lingering concerns about the virus, uncertain school schedules, unavailable affordable childcare and a spike in retirements. There was also an up-skilling of a significant number of furloughed workers during time away from jobs. When these individuals did return to the labor market, they were able to take positions in higher-paying jobs. The economy saw a reallocation of labor during 2021.

North Carolina ended the year on an upbeat note with the announcement of the multi-billion-dollar Toyota plant in the Triad that will produce electric batteries for vehicles. This prize capped a year with $10 billion of new business investments announced for the state.

Outlook for 2022: Growth Forecasts

North Carolina has the momentum to have another good economic year in 2022. In 2021, the state was the fourth fastest in total population growth and was also a leader for migration of households from other states. North Carolina continues to have advantages in total cost of living, cost of doing business, the cost of higher education (North Carolina ranks sixth lowest among states in annual tuition and fees at public four-year institutions), natural amenities and climate.

Economic improvement in 2022 should continue, although somewhat less robustly than last year since the economy was still rebounding from the pandemic’s 2020 recession. Aggregate production should increase 3.5%, 100,000 net new jobs could be created, and the unemployment rate will likely end the year at near 3.6%. The fastest growing sectors for jobs will be hospitality and leisure services, professional and business services and technology.

Metropolitan areas in the state, particularly the Triangle, Triad, and Charlotte should again be leaders in growth. However, economic gains in 2022 will spread to more geographical regions in the state. As the economy grows, and prime sites in large metropolitan areas become relatively more expensive, there is a natural incentive for investors to look for less costly locations. Counties in large metro areas but farther from the core city will benefit from this trend, such as Chatham, Franklin and Lee in the Triangle, Cabarrus, Gaston, and Stanly near Charlotte, and Alamance, Davidson and Randolph in the Triad.

If the geographic availability of high-speed internet significantly expands in 2022, less-populated regions could also experience faster growth. This is already happening in Greenville and Hickory. With internet availability – now considered a necessity in the modern economy – even smaller communities could share in business and population expansion. Both the federal and North Carolina state governments have allocated new funds for internet provision in underserved locations. An additional player will be the private sector company Spacelink, an effort by entrepreneur Elon Musk to link the world with internet service using low orbiting satellites. Musk has said the initial provision will occur in 2022.

The New Uncertainty

While the economic outlook for North Carolina is positive, it is important to realize the state’s future is still subject to forces beyond its control. One obvious force that fits this category is the Covid-19 virus and its variants, which have dominated the world during the past two years.

Medical experts say variants may continue to emerge, as the Omicron variant did at the end of 2021. While such variants may cause some curtailments of public events and increased efforts for more vaccinations, many experts don’t see them resulting in the business shutdowns and stay-at-home orders of spring 2020. Instead, they foresee countries developing improved methods for coping with Covid-19, while at the same time allowing for most of life to continue. This optimistic outlook will be proven wrong if a deadlier and more unpredictable variant emerges.

A new source of uncertainty is the future policy actions of the central bank of the country, the Federal Reserve, or the “Fed.” The inflation rate in the prices of products and services surged to 40-year highs in 2021. While there is debate over the causes, one contributing factor is likely the “easy money” policy of the Fed during the pandemic. To help the country cope with and then recover from the virus, the Fed kept its interest rates at historic lows and created money to support the federal government’s stimulus programs. Both actions can be inflationary, and many economists suspect they were.

The question is, how hard will the Fed push on the brakes?

Now the Fed is signaling it will reverse course in 2022 and raise interest rates and moderate money creation. The question is, how hard will the Fed push on the brakes? Optimally, the Fed would move cautiously and slowly reduce the inflation rate without disrupting economic growth. But as we witnessed in the late 1970s when the Fed took similar actions, this is a “difficult needle to thread.” One viewpoint is the Fed will have to move boldly to make any progress against fast-rising prices. If large interest rate increases are paired with slow – or no – growth in the money supply, then economic growth in the second half of the year – even in booming North Carolina – could be on the chopping block. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that the Fed’s “tightening” strategy could push the economy to a recession in late 2022. Of course, a nationwide recession would imperil growth prospects in North Carolina in 2022 as well as present potential losses to investors. Economic development projects would be put on hold and the state budget would likely be tightened.

Preparing for the Longer Run

It is never too early to think about North Carolina’s long-term future. Although the state’s economic path in upcoming decades should be more positive than for many states, there will be issues and challenges that, with enough foresight, North Carolina can successfully address.

One may be an issue the state is currently experiencing – a labor shortage. Although current projections from the State Demographer and analysts in the state Department of Commerce show the number of workers and number of job positions increasing at the same pace, there could still be labor shortages in two ways.

One is a possible geographic shortage, meaning the number of new jobs in a specific region may not match the number of new workers in that same region. The shortages will mainly occur in fast growing metropolitan areas, while surpluses will be more prevalent in several rural regions. State policies facilitating the movement of labor from surplus regions to shortage regions should be considered.

The second labor shortage could be in training. Technological developments will continue to move jobs away from those using low-skilled labor to perform routine tasks to jobs applying high-skilled labor for cognitively challenging tasks. The question is whether education and training will keep up with the changes. Many of the cognitive-based occupations will require formal training beyond high school and while two-thirds of high school graduates in North Carolina enroll in a 2 or 4-year college, a large number do not graduate, and others follow majors that are not in demand. The state budget passed in 2021 provided additional funds for schools. Successfully navigating future needs will require a thorough examination of the state’s educational institutions regarding both programs and funding.

International competitiveness is another long-run issue. While the U.S. – and North Carolina – are leaders in many economic sectors, other countries are rapidly developing and improving. The next several decades will see increased competition from India, Vietnam and Africa. Advances in technology will continue to expand worldwide trade. This is another reason why North Carolina must continually evaluate all levels of its educational system to ensure our students and workers are keeping pace with the world.

The Next New North Carolina

North Carolina has remade its economy several times. Now, as the state, country and world emerge from the Covid-19 pandemic, a new North Carolina is likely to emerge, with 2022 being the starting point.

The next new North Carolina will be based – just as the previous versions have – on new technology. Artificial intelligence, virtualization and digitalization will be the leaders in the next version of the state. It is difficult to comprehend what the state will look like in a decade, and certainly in two decades. How and where people work and live, how they shop and engage in important services like education and health care, and how both products and services are generated and delivered, will determine the future.

Futurists agree the pandemic has accelerated these developments, meaning the next new North Carolina will arrive sooner than it would have without Covid-19. Hopefully this will be a lasting positive legacy of the pandemic.

Editors for this issue of the NC State Economist

Roger von Haefen, Professor

Margaret Huffman, Communications Coordinator